Stay Seen, Stay Safe. For the last 14 years, beginning in Bicycling & the Law, and continuing in Legally Speaking, Road Rights, and the Bicycle Law blog, I’ve consistently advocated that cyclists can minimize the risk of a car-on-bike collision by helping drivers to see them.

This is not just “common sense,” or wishful thinking. The science is solid on this point:

- There is a 7:1 size differential between cars and bicycles. You can mitigate this size differential visibility advantage that cars have by helping drivers to see you better.

- Most car-on-bike collisions occur at night.

- Perception distance is the distance at which a driver can first see you. This means that the driver sees something (you) but hasn’t yet recognized what that something is (a cyclist).

- Recognition distance is the distance at which a driver can first recognize that you are a cyclist. Recognition distance is a shorter distance than perception distance, because after first perceiving that there is something (you) on the road, it takes time for the driver to recognize that you are a cyclist.

- The nighttime perception distance for dark clothing is only 75 feet. At speeds of 60 MPH, this gives drivers less than a second to react once they first perceive the cyclist. Even at speeds of 30 MPH, drivers have less than two seconds to react once they perceive the cyclist.

- The nighttime perception distance for reflective material ranges from 1,200 to 2,200 feet.

- The nighttime recognition distance for reflective material ranges from 600 to 700 feet in darkness but decreases to 260 to 325 feet with brighter background lighting.

- The daytime perception distance for hi-viz clothing can increase from 400 feet to 2,200 feet. The nighttime perception distance for hi-viz clothing can increase from 150 feet to 560 feet.

To help drivers see cyclists better, there are a number of conspicuity-enhancing strategies we can and should follow to help drivers see us. Recently, I had an unexpected opportunity to see these conspicuity-enhancing strategies in the real world. I was in Silicon Valley for an event; the venue was in Cupertino, California, right along the border between Cupertino and Sunnyvale. Both cities have been designated as Bronze-level Bicycle Friendly Communities by the League of American Bicyclists, and this designation was proudly noted along the road that borders the two cities.

As I was walking to the venue, I noticed a large group of bicyclists, totaling about 20 people, who seemed to be part of a guided bicycle tour. As the group was waiting for the traffic light to change, what really stood out and grabbed my attention was their attire– every one of the cyclists was wearing a fluorescent yellow-green safety vest. In fact, the fluorescent safety vests were so effective at capturing my attention that I didn’t even notice that all of the cyclists were stopped at the traffic light, and had completely failed to be the scofflaws the haters commonly accuse cyclists of being.

There’s a psychological phenomenon called confirmation bias that explains why some drivers will proclaim that “Bicyclists DO NOT FOLLOW LAWS…EVER,” despite abundant evidence that many cyclists do follow the laws (and likewise, that many drivers do not follow the laws). Confirmation bias is what happens when we look for evidence that supports our pre-existing views, and disregard or ignore evidence that challenges our pre-existing views.

Here’s how confirmation bias works: If you’re a driver who believes that “Bicyclists do not follow laws…ever,” you’re going to find numerous examples of cyclists breaking the law. Some of those examples will actually be instances of blatant law-breaking. But some of them will be instances of the cyclist following the law, but with the driver either not knowing or not caring what the law says. Once you’ve made up your mind that cyclists are lawbreakers, you’re not going to be swayed by facts that contradict your belief.

Confirmation bias is a two-way street, too. If you’re a cyclist who believes that all drivers are out to murder us, you’re going to find numerous examples of drivers doing careless things that could injure or kill you (and it’s not at all difficult to find such examples), and you’re also not going to notice the numerous examples of motorists driving carefully and courteously.

But that day in Sunnyvale, I wasn’t looking for evidence of cyclists breaking the law, or obeying the law. I was just looking for the entrance to my venue, when I happened to notice a large group of cyclists all wearing fluorescent hi-viz safety vests. And as other cyclists rode by, I noticed they were also wearing fluorescent hi-viz safety vests or jackets.

This should have felt like a victory of sorts. Virtually every cyclist on the road was following the kind of safety recommendations I had been advocating for years. The word had gotten out…and yet it didn’t feel like a victory at all. As I looked at cyclists riding along the road that day, all wearing hi-viz clothing, I couldn’t help but think “What have we done?”

Not “we,” as cyclists, nor “we,” as cycling safety advocates. But we, as a society– what kind of roads have we created where cyclists must take extraordinary precautions in the hope that they will return home alive? Cyclists are advised to wear hi-viz, to ride with lights even in daytime, and to wear a helmet, even though bicycle helmets are not designed to protect against the kind of high-impact collisions of a car-on-bike crash. That may seem “normal,” but would it seem equally normal if we advised drivers to buy cars in hi-viz colors, to run their headlights even on a sunny day, and to wear helmets while driving? What if we advised people to be sure to wear a fluorescent yellow safety vest, flashing lights, and a helmet whenever they walk? Would that seem “normal” too?

That’s not to say that drivers don’t have safety protections, but their safety protections are required, and built-in: Seatbelts, crumple zones, side-impact protection, airbags, all required and built-in. If you think about it, however, the safety protections we require for drivers are directed towards minimizing injuries to the driver and occupants at the moment of impact in a crash. They don’t do anything to prevent the crash from happening in the first place, which is the goal of safety precautions like hi-viz clothing. At best, manufacturers equip cars with better braking systems, but those are designed to offset (and are offset by) the speeds generated by more powerful engines.

It’s not just the speeds generated by cars that are dangerous. When set too high, speed limits themselves lead to more crashes, particularly when they go unenforced. And most dangerous of all are vehicles that are traveling at significantly higher or lower speeds than other vehicles on the same roadway.

Which is exactly what happens when we set a higher speed limit on a roadway that is shared by automobiles and bicycles. In the United States, we recognize that cyclists are often incapable of traveling at the same speed as drivers by painting a line on the road, and requiring drivers to drive on one side of that line, and cyclists to ride on the other side of that line.

A line of paint.

That’s all that separates cyclists from multi-ton vehicles moving two or more times faster than the cyclist. Cyclists with years of experience riding in traffic may feel inured to a sense of danger, but for most people who aren’t already experienced cyclists, the sense that their life is in danger can all-too-easily become their overall cycling experience. Inexperienced cyclists may believe that the painted lines on the roadway (aka “the bike lane”) will protect them, right up until their first close call.

Hi-viz does work. But so does paying attention when you’re driving. Just yesterday, I was driving on a country road as sunset was approaching. Visibility was dropping along the forest-lined road, and up ahead were 3 bicyclists, all wearing grays and other subdued colors. I saw them, even without hi-viz and lights, because I was paying attention. I would likely have seen them much sooner if they were wearing hi-viz, because that’s what hi-viz does for you, but I saw them nonetheless. As I’ve said previously,

“It’s really a miracle that careless drivers don’t injure and kill more cyclists than they already do. And yet when a cyclist is injured or killed by a careless driver, the number one excuse the driver will make is “I never saw the cyclist.” It’s like a talisman that magically wards off accusations of negligence: “I never saw the cyclist.”

But it’s not a talisman. It’s not an excuse. It’s not even an explanation.

Rather, “I never saw the cyclist” is almost always an admission of negligence.”

Every cyclist wearing hi-viz looks like a victory for cyclist safety, but in fact, it’s not a victory, it’s just one more way we’ve shifted responsibility for cyclist safety away from drivers, and onto cyclists themselves. There’s a very good reason we have to take our own safety seriously– because drivers don’t take our safety seriously, our traffic agencies don’t take it seriously, our legislatures don’t take it seriously, and our law enforcement and legal system doesn’t take it seriously. So while it’s important for us to be attentive to our own safety, we shouldn’t get comfortable with thinking that it’s good enough if we take our own safety seriously. It’s not good enough. There has to be a better way to protect people’s lives when they’re on bikes. And in fact, there is a better way. I’ve also said previously that

“There’s a different kind of ripple effect—the kind of positive ripple that comes when people see that their safety is taken seriously, and that cycling is safe, not just for the strong and fearless, but for “everybody from 8 to 80.” We know this positive ripple exists, because we can see the results where people know that their safety is a societal priority, in the Netherlands, and in Denmark. The sheer numbers of people—everyday, ordinary people who may not even think of themselves as “cyclists”— riding in these countries demonstrate that when people feel that their safety is taken seriously, they will ride. It’s not necessary to be a strong and fearless rider, or a risk-taker, or specially-trained, or to wear helmets and lights and fluorescent colors. It’s just necessary to prioritize cyclist safety, to stop shifting the blame for collisions from careless drivers to their victims, and to stop normalizing and excusing dangerous driving. When we do these things, people feel safe, and they will ride, because they know they will come home safe at the end of the day.”

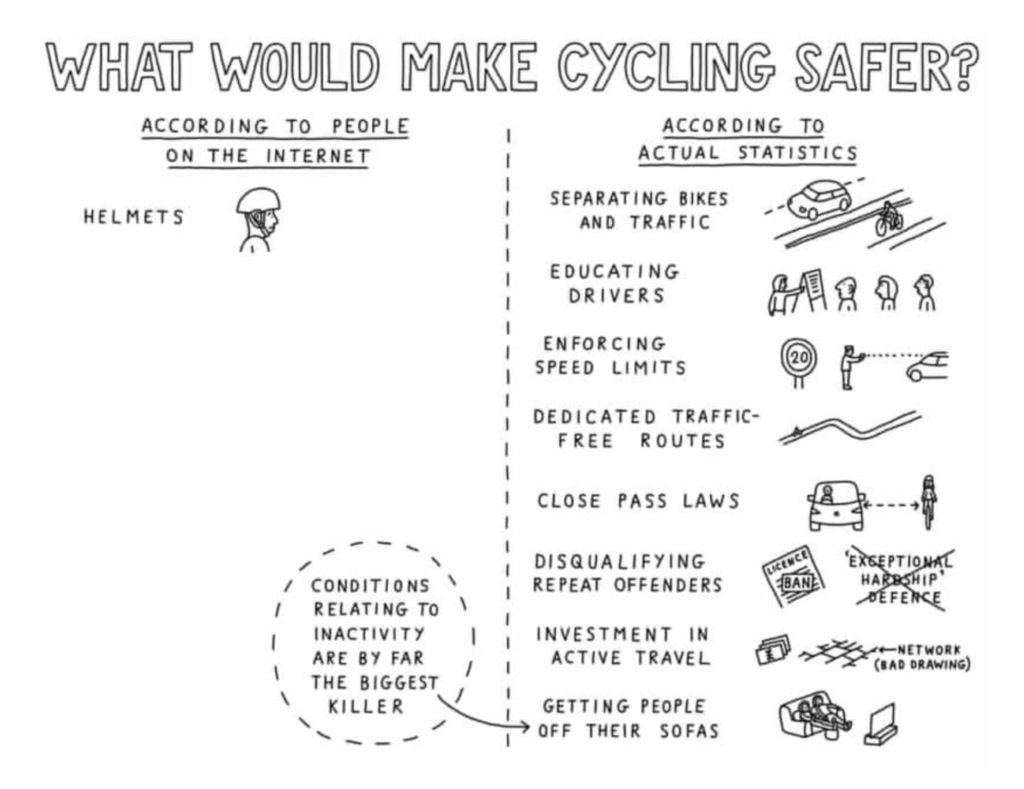

And that really should be the goal of any bicycling-friendly community, shouldn’t it– for people to feel so safe riding their bike that they know they’ll come home safe at the end of the day? That kind of safety– real safety– doesn’t come from painted lines on the road, or bicycle helmets, or hi-viz. It comes from the things that have been proven to work: Separated bike lanes, dedicated traffic-free routes, and bicycle highways; holding drivers to higher standards for obtaining and keeping a driver’s license; shifting the burden of proof in traffic collisions from cyclists to drivers; lower speed limits on streets where it’s not possible to separate automobile and bicycle traffic; close pass laws; passing laws that fill in the legal “donut hole” between minor traffic violations and reckless driving; and enforcement of laws protecting cyclists from dangerous driving.

These are the approaches to traffic safety that have been adopted in countries where cyclist safety is taken seriously, and where as a consequence large numbers of people ride their bikes, because it feels safe for “everybody from 8 to 80.”

But we live in this country. So should cyclists wear (or continue to wear) hi-viz? On roads where cyclist safety is not taken seriously (that is, on virtually every road in this country), hi-viz can help cyclists stay seen and stay safe. Can we do more?

Yes.

We can and should do more. Much more.

***

Bicycling is a safe and healthy activity, and with appropriate precautions and attention to your safety, bicycling is even safer. Real progress to make bicycling even safer is possible, but we’re not there yet. Nevertheless, no sporting activity is ever completely safe. Despite your best efforts, there will always be some small possibility of injury. Regardless of whether a bicycle accident is a solo accident, or involves a collision with an automobile, or a defective cycling product, the accident is usually the result of somebody’s negligence– the driver’s negligence, the cyclist’s negligence, both the driver and the cyclist, or the local government responsible for the condition of the roads and trails.

If the negligent party in that crash is the driver, (or the government agency responsible for the roads, or even the manufacturer of a defective bicycle product), the cyclist has a legal right to be compensated for his or her injuries.

If you have been injured while riding, contact bicyclelaw.com or another personal injury attorney who understands bicycling. While many attorneys are competent to handle general injury cases, make sure your attorney has experience and is familiar with:

- Bicycle traffic laws

- Negotiating bicycle accident cases with insurance companies

- Trying bicycle accident cases in court

- The prevailing prejudice against cyclists by motorists and juries

- The names and functions of all bicycle components

- The speed bikes travel as well as braking and cornering

- Bicycle handling skills, techniques, and customs

- How to get the full replacement value property damage estimates for your bicycle

- Establishing the value of lost riding time

- Leading bicycle accident reconstruction experts

- Licensed forensic bicycle engineers

- Establishing the value of permanent diminished riding ability

If you have been injured in a bicycle accident, whether in a solo accident that may be the result of another party’s negligence, or in a collision with another person, contact bicyclelaw.com for a free consultation. Bicycle Law has offices in California and Oregon.

If you want to speak to us about a crash, your rights, or an advocacy matter, please call (866) 835-6529 or email info@bicyclelaw.com.