San Francisco

It was Wednesday evening, rush hour, and hundreds of cyclists had gathered together at a San Francisco intersection to begin their rush hour ride. But this was no ordinary rush hour ride home. The cyclists, who were operating as traffic, had gathered to make a point: Every cyclist intended to come to a full and complete stop at every stop sign and red light.

As is the case throughout our country, cyclists in San Francisco had been abused as “scofflaws” for years by drivers who take a dim view of cyclists rolling through stop signs, instead of coming to a full and complete stop. (Ironically, motorists actually break the law more often than cyclists). Cyclists had had enough, so they were about to give motorists a taste of what they had been saying they wanted.

As the cyclists took to the street, their point became clear: “traffic” (including both motorists and cyclists) slowed to a standstill while each cyclist patiently slowed, came to a complete stop, and put a foot down before slowly starting up from the complete stop and moving on to the next intersection. Frustrated motorists, who had become habituated to complaining bitterly about cyclists who roll through stop signs, were now experiencing exactly what they had demanded. And as drivers frantically attempted to escape the traffic snarl by driving in the wrong lanes, it became clear that while cyclists scrupulously obeying the law was what drivers said they wanted, in practice it was not what drivers wanted at all.

Police, whose recent vow to crack down on lawless cyclists had triggered the “Stop-In,” watched helplessly as the street became a tangled snarl of rush hour commuters stuck in a quasi-parking lot, going nowhere any time soon. Attempting a show of bravado, the police threw their own police vehicles into the tangled mess, thanking the cyclists over their loudspeakers for obeying the law. But really, there was nothing else the police could do; the cyclists were traffic, and they were obeying the law. A laughable display of false bravado was the only hand the police had.

The cyclists, on the other hand, weren’t merely suggesting that they should be allowed to break the law. In fact, the protest was intended to demonstrate that the reasonable solution to the question of how cyclists should behave at stop signs was for the city to pass a law allowing cyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs. In other words, cyclists were saying if it became legal for cyclists to yield at stop signs instead of coming to a complete stop, then traffic would flow more smoothly, and cyclists would no longer be stigmatized as scofflaws and penalized for yielding at intersections.

It was a concept that made sense to every cyclist there. But the accepted order of things was being challenged, and that left drivers and police alike confused and angry. Yet few if any people present at the “Stop-In” that day knew that the origins of the conflict began some 2,400 miles away, in Detroit, Michigan.

Detroit

The boy, 18 months old and the child of immigrants, had been hit by a car, his lifeless body wedged in the car’s wheel well. While his hysterical father and Detroit police worked frantically to free him from the machinery that had taken his life, his mother went back into the house and took her own life. The tragedy was complete.

And it wasn’t a rare tragedy. 60 percent of all automobile fatalities nationwide were children under the age of 9, and excessive speed was the main cause of these fatal collisions.

Nearly 100 years later, in 2018, a 20-month old child in was hit by a car and fatally injured in Pontiac, Metro Detroit. The more things change, the more they remain the same.

Well, some things remain the same, but some things do change. Today, when drivers kill, we shrug collectively. Traffic fatalities—the equivalent of two jumbo jet crashes every week, all year long—are an accepted feature of contemporary life, not even worthy of anything more than the occasional sad-faced emoji. With the magic words “It was just an ‘accident’,” we collectively absolve the careless driver from any real responsibility for the life that was carelessly taken. “There but for the Grace of God go I,” we acknowledge to ourselves. Consequences for taking a life are only meted out for particularly egregious behavior—typically involving DUI, hit and run, or reckless driving. Ordinary carelessness—for example, “I didn’t see the cyclist” in broad daylight—is so normalized that police openly sympathize with the driver, while the rest of us offer bromides about how the driver will suffer pangs of conscience even though there are no consequences.

But 100 years ago, the public had a very different attitude towards traffic fatalities. In the early years of the 20th century, the streets were already teeming with traffic, primarily pedestrians, horses, streetcars, and cyclists. And then, beginning in the late 1890s, automobiles were added to the traffic mix. The results were immediately disastrous. The first automobile accident in which somebody was injured occurred in New York City in 1896, when motorist Henry Wells crashed into cyclist Evelyn Thomas. Thomas suffered a broken leg, while Wells was arrested and taken to jail.

The first fatal automobile accident also occurred in New York City, in 1899, when a taxi cab veered into the path of Henry Bliss as he stepped off a streetcar. The cab ran over Bliss, crushing his head and chest under the wheels. Arthur Smith, the taxi driver, was arrested and charged with manslaughter. Newspapers did not comment on whether Bliss was wearing a helmet.

Smith was later acquitted of the manslaughter charge, because he was found to have acted with neither intent nor negligence.

Henry Bliss

As automobiles continued to grow in numbers on our roads, the toll of injuries and fatalities began to soar, and as the numbers of victims soared, public outrage also soared. Drivers—labelled “remorseless murderers” by the newspapers—were charged with murder and manslaughter when pedestrians were killed. For other violations of the law—typically speeding, which was viewed as the primary factor in the mounting casualties on our roads—they were punished with stiff fines and jail time. And yet cars continued to pour onto our roads in ever-increasing numbers, and with them, injuries and deaths continued to skyrocket. The public, outraged, demanded action, but the police were overwhelmed by the sheer number of automotive scofflaws on the roads. Something had to be done—but what?

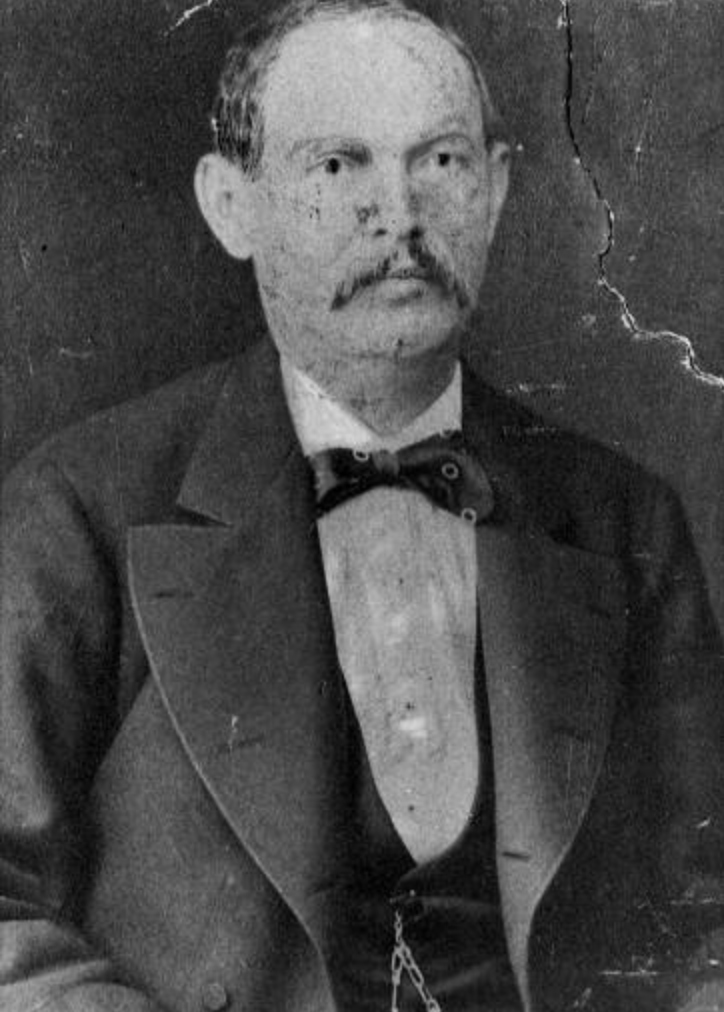

In Detroit, ground zero of the U.S. auto industry, a former Ford Motor Company executive named James Couzens stepped into the unruly fray, determined to bring a situation that had become a public relations nightmare for the automotive industry under control. Couzens had sold his shares in stock back to Ford for $30 million in 1919 (an amount equal to $441.45 million today) after he had a falling out with Henry Ford. He then began a career in public office, serving first as Detroit’s Commissioner of Street Railways, then Police Commissioner, Mayor, and eventually, United States Senator.

James Couzens

Couzens developed a new approach to street safety: He argued that adult pedestrians were equally at fault for the death toll, because of behaviors like careless street crossing and what we now call “jaywalking.” Couzens’ solution to pedestrian casualties was to remove pedestrians—a part of traffic since time immemorial—from the street, by forcing them to cross streets at designated corners. If pedestrians continued to cross streets as they always had, they were now branded as careless. The blame had been shifted from careless motorists to their victims.

The other approach Couzens developed was to implement new technology to enforce order, including stop signs and traffic lights at intersections. The first stop sign in the nation had been installed at a Detroit intersection in 1915, while Couzens was still at Ford, but under Couzens traffic control technology became widespread in Detroit. Other cities across the nation were pursuing similar traffic safety reforms. At the national level, it had become obvious by 1923 that a uniform traffic law was necessary in the various states, and in 1924, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover set in motion the beginnings of a Uniform Traffic Law for the states to adopt. To this day, the Uniform Traffic Law still serves as the suggested basis for state traffic laws and is regularly updated to reflect new developments in traffic.

Cyclists, who had organized to fight for their right to the road through the League of American Wheelmen (now the League of American Bicyclists), had been gaining the legal right to the road since 1887. The other side of that coin was that by gaining legal rights, they had also acquired corresponding legal duties. And thus, gradually, cyclists were also brought within the traffic laws that were being developed nationwide.

But even as cyclists were brought within the laws, they, like pedestrians, were also being pushed off the roads. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the automobile continued to gain an increasing dominance on the roads, with cyclists and pedestrians relegated to the margins, and in many cases, removed from the roads altogether.

By the 1950s, the automotive revolution seemed complete; pedestrians and cyclists had been pushed off the roads for the most part, the automobile was virtually unchallenged in its dominance, the laws reinforced this order. The previous order had been turned upside down. Where the automobile had once been seen as a dangerous, unwelcome intruder on the public space, it was now people on bikes and on foot who were seen as unwelcome intruders on the public space. Where motorists were once blamed for the injuries they caused, it was now their victims who bore the blame for their own injuries.

This shift in attitude was apparent in all strata of American society, from the media, to public opinion, to the law, to law enforcement: Cyclists didn’t belong on the road, and if they were injured by a careless driver, it was their own fault. As one advocate put it, “The culture of law enforcement in bicycle accidents is you blame the victim: What the hell was she doing on a bike? What the hell was she thinking?”

And yet, improbably, at the moment when the primacy of the automobile most seemed to be a fait accompli, people fell in love with the bicycle all over again, in the third great bike boom. And with more people than ever riding bikes, the stage was set for the most serious challenge yet to the new road order.