Some see things as they are, and ask why. I dream of things that never were, and ask why not.

– Robert F. Kennedy

From its earliest beginnings on American roads, the automobile had been a rude and dangerous interloper. Reckless drivers, labeled “remorseless murderers” by the newspapers, ran amok with abandon, leaving dead and injured Americans in their wake in ever-increasing numbers with each passing year. The public, outraged by the toll of dead and injured in our streets, demanded that the automobile be brought under control.

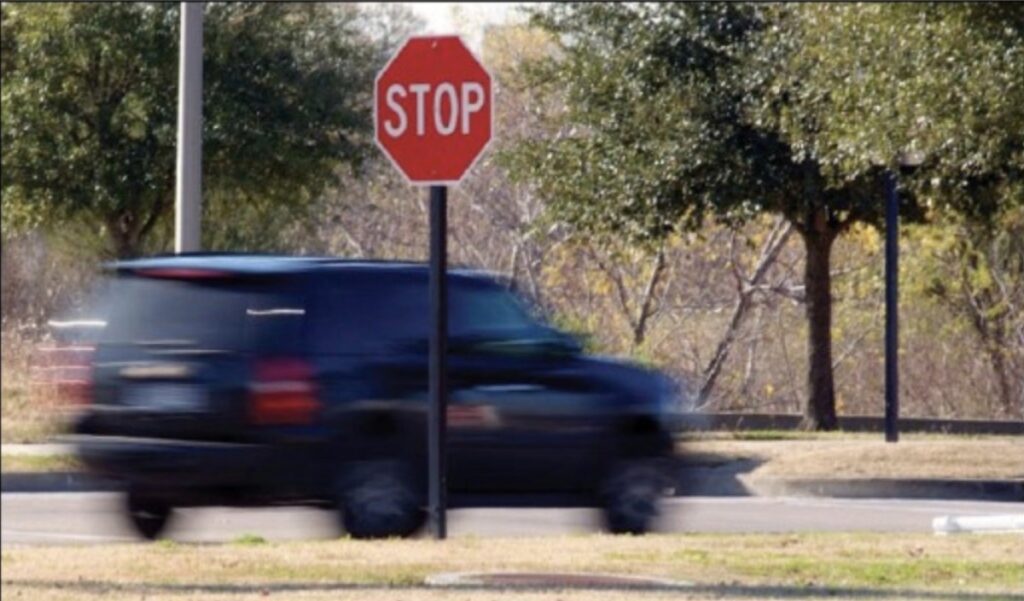

Overwhelmed by the automotive onslaught, authorities responded to the public outrage in a three-pronged approach. First, the problem was re-defined by shifting the blame from reckless drivers to their victims. Pedestrians, who had been a part of street traffic since time immemorial, were removed from the streets altogether, save for designated crossing areas at intersections; cyclists were increasingly pushed to the margins of the roads, out of the way of the drivers who were now claiming the roads as their exclusive territory. Second, new technology—primarily stop signs and stop lights—was introduced to our streets to bring some order to the flow of traffic at intersections. And third, a concerted effort to develop standardized traffic laws across our nation was undertaken.

Over the better part of the 20th century, the automobile’s ever-expanding dominance of American roads continued; this dominance was cemented by an ongoing and continuously evolving project to normalize the automotive takeover of our public spaces and its attendant slaughter of thousands of Americans each year by careless drivers. By the time this project to normalize automotive dominance entered its 9th decade, a third great bike boom had come and gone, and across the nation, states began to revise their traffic laws, downgrading most violations of the traffic laws from crimes to infractions.

And thus, in 1982, Idaho was deep in the process of revising its own traffic laws, with the goal of reducing most minor traffic offenses from misdemeanors to “civil public offenses.” Carl Bianchi, then Administrative Director of the Courts in Idaho, saw an opportunity to revise the state’s bicycle laws, bringing them into close conformity with the Uniform Vehicle Code, and agreed to draft a new bicycle code. And because the state’s magistrates had been complaining about the number of tickets that law enforcement had been writing for cyclists who didn’t come to a complete, foot-down stop, Bianchi drafted a new law that would address the concerns of the magistrates: Under the proposed new law, cyclists would be allowed to treat stop signs as yield signs. The Idaho legislature passed the revisions to the traffic laws that year, and thus, almost improbably, “Stop as Yield” became the law in Idaho.

The Idaho Stop—What Is It?

Here’s how it works in Idaho: When a cyclist approaches a stop sign in Idaho, the law says that the cyclist may treat the stop sign as if it is a yield sign. This means that the cyclist is required to slow to a reasonable speed when approaching the intersection, and “stop if necessary for safety.” The law continues: “After slowing to a reasonable speed or stopping, the person shall yield the right-of-way to any vehicle in the intersection or approaching on another highway so closely as to constitute an immediate hazard…” However, if the cyclist has the right of way at the intersection, the cyclist may slow to a reasonable speed and roll through without stopping or yielding. This is exactly how a yield sign works, which is why the law is usually called “Stop as Yield.”

The Idaho law also has a “Red as Stop” clause, added to the vehicle code in 2006, which means that cyclists are required to stop at a red light, but after yielding to all other traffic, may proceed through the intersection without having to wait for the light to turn green. This is exactly how a stop sign works, which is why the law is called “Red as Stop.”

The Shape of Things to Come?

Bob Mionske supporting Stop as Yield, Oregon Legislature 2009

For decades after, Idaho remained the only state in the nation with a “Stop as Yield” law. Cyclists in other states looked on with envy, wishing their own states would pass a Stop as Yield law. And in fact, efforts were made to pass a Stop as Yield law in several states, but every effort went down in defeat. In 2017, California looked like it might be the second state to pass a Stop as Yield law, but that effort too went down in flames.

And yet although Stop as Yield was defeated in California, Delaware passed a limited version of Idaho’s Stop As Yield Law that same year. After 35 years, the logjam of resistance to Stop as Yield had begun to break. The following year, Colorado passed legislation that standardized Stop as Yield language, and giving cities and counties the option to adopt a local Stop as Yield law with that language. Neither the Delaware nor the Colorado legislation were complete Stop as Yield laws in the vein of the Idaho law, but they were clear evidence that opposition to the Stop as Yield concept was buckling.

Then, on April 1 of this year, Arkansas passed a full Idaho-style Stop as Yield law, officially becoming the second state in the country to adopt the Idaho law in its entirety. By April 10, the Oregon Senate was considering its own version of a Stop-as-Yield Law, and on June 5th the Oregon legislature passed its own Stop as Yield law. Oregon was now on the cusp of becoming the 4th state in the union with a Stop as Yield law. The tide was clearly turning.

For 35 years after Idaho passed its Stop as Yield law, it had remained a tantalizing legislative goal for cyclists in other states, always just out of reach. But over time, something changed—the concept of Stop-as-Yield began to seem less preposterous, more reasonable. Did the arguments finally begin to make sense? Did people just need time to get used to the idea? Whatever it was that had changed, we are now at 4 states with a Stop as Yield law.

Will California Be Next?

It’s virtually certain that there will be continuing legislative efforts in other states, including California. But will California be the next state to pass a Stop as Yield law? It would be easy to argue that it’s too soon after the 2017 defeat. California’s Stop as Yield bill was opposed by powerful forces, including both the insurance industry and the Teamsters.

But let’s consider the arguments of the opponents for a moment. AAA (the American AUTOMOBILE Association, hint hint!) argued that Stop as Yield would be unsafe and “detrimental to all road users.” This is the stuff of alternate realities. Until the automobile industry flipped the script, it was the automobile that was considered “unsafe and detrimental to all road users.” Now, with a straight face and not a shred of evidence, the California branch of a national federation of motor clubs claims that it’s really cyclists yielding at intersections who pose a threat on our roads. In fact, the opponents of the Stop as Yield legislation were as opposed to gathering data about Stop as Yield as they were to passing a Stop as Yield bill.

In opposing Stop as Yield, AAA was pushing a century of automotive propaganda that painted the victims of careless and reckless drivers as “unsafe.” But the truth is that drivers not only break the law more often than cyclists, they are also by far the greatest danger on our roads.

The Teamsters’ argument opposing Stop as Yield was that it “would insert unpredictability into the traffic safety equation.” Let’s unpack that. You know how when you arrive at a 4-way intersection controlled by stop signs, and someone in cross-traffic arrives at more or less the same time? You both have that moment of uncertainty when you’re trying to decide who has the right of way, and wondering whether you both agree on that point. That’s called “driving.” The uncertainty is not only completely normal, it creates the momentary pause that is necessary for people to safely get through the intersection. You know who barrels through intersections with utmost certainty about who has the right of way? People who cause accidents. Replace some of the stop signs at that intersection with yield signs, and you still have the uncertainty necessary for people to safely cross intersections.

In short, the arguments opposing Stop as Yield in California are not actually formidable. They’re the product of lazy thinking that relies on prejudice and resistance to change. To be sure, appeals to prejudice are powerful, but lazy thinking is not, and appeals to prejudice shouldn’t be confused with rational argument or sound judgment.

Furthermore, opposition to the Stop as Yield bill wasn’t universal; the Editorial Board of the Los Angeles Times got the concept of Stop as Yield, coming out in favor of the legislation. There’s a sea change underway in how we think about Stop as Yield, in California and across the nation, and the logjam of opposition to Stop as Yield will break again.

But is it too soon to try again in California? I don’t think so. In fact, now that a new Governor has replaced Jerry Brown, who proved to be unusually hostile to cyclists during his second incarnation as Governor, and with the Governor’s party holding a supermajority in the state legislature, there has never been a better time to advance a pro-cycling legislative agenda.

Why we should Greenlight Stop as Yield

The arguments against Stop as Yield are really just lazy appeals to prejudice. To be sure, appeals to prejudice can be powerful persuasion, but they’re weak arguments. Stop as Yield, on the other hand, has some very powerful arguments in its favor. Rather than creating a free-for-all on our roads, Stop as Yield keeps both cyclists and motorists within the framework of the law, while recognizing the differences between bicycles and cars. Currently, we insist upon “Same road, same rules” logic, even though that isn’t actually logical because of fundamental differences between bicycles and cars. The more rational approach to the law would be “Same road, same rights, different rules.”

The reason should be obvious. Bicycles inhabit a kind of middle-ground between a pedestrian and a motor vehicle. They’re not exactly like a pedestrian, and they’re not exactly like a motor vehicle either. If we don’t make pedestrians follow all of the rules for motorists (note, for example, that pedestrians are not required to stop at stop signs), and we don’t make motorists follow all of the rules for pedestrians, why do we insist on shoehorning cyclists into rules that aren’t a good fit? Why don’t we have rules for cyclists that recognize that we’re neither pedestrians nor motorists, while still respecting our rights to the road?

It’s not even a radical idea. We already recognize, for instance, that California cyclists can take the lane when they are riding at the normal speed of traffic, but must ride to the right when they are riding at a speed less than the normal speed of traffic. This is a clear example in California law that we do in fact recognize that bicycles and cars are not exactly alike, and therefore, will sometimes have different rules. Because there are differences between our different modes of transportation, it’s more rational to conform the rules of the road to people, than it is to try to conform people to the rules of the road.

And when it comes to stops, the main difference between cyclists and motorists is conservation of momentum. When a driver starts from a full stop, he only has to press the gas pedal a bit, and off he goes. When I start from a full stop, I have to call on my muscles to get me back up to speed and across the intersection.

It would be easier and safer if I could just maintain my momentum when there’s no cross-traffic. But because stop signs are often ubiquitous on the less-busy streets cyclists often favor, it would be illegal for me to maintain my momentum. I’m required by law to come to a complete stop, even when there’s no cross-traffic (full disclosure: I actually do stop.) This is not only unnecessary for safety, it actually makes my ride less safe, because as I’m crossing the intersection, I’m also coming from a dead stop back up to speed, which means I have the least amount of momentum and stability just as I’m entering the intersection.

It would be far safer for me to slow to a reasonable speed when approaching the intersection, and stop if necessary for safety, yield the right-of-way when required, and roll through without stopping or yielding when the law allows. This is exactly how a yield sign works, so again, it’s not even a radical concept.

But is it safe? According to the Idaho Transportation Department, there has been “no discernible increase in injuries or fatalities to bicyclists.” In fact, the first year after the Stop as Yield law passed, injuries to bicyclists actually decreased by 14.5%. In other words, decades of real-world experience on Idaho’s roads demonstrate conclusively that Stop as Yield is safe.

It’s taken 35 years, but we’re finally seeing states wake up to the reality that our bicycle laws could actually be safer and better for all road users. Will California be next?