With a brand-new year still stretching out before us, full of promise and hope, it’s a natural time to think not just of what the year will bring to us, but of what we will bring to the year. With that in mind, here is the 3rd of 6! five improvements we can make to California’s bicycle laws.

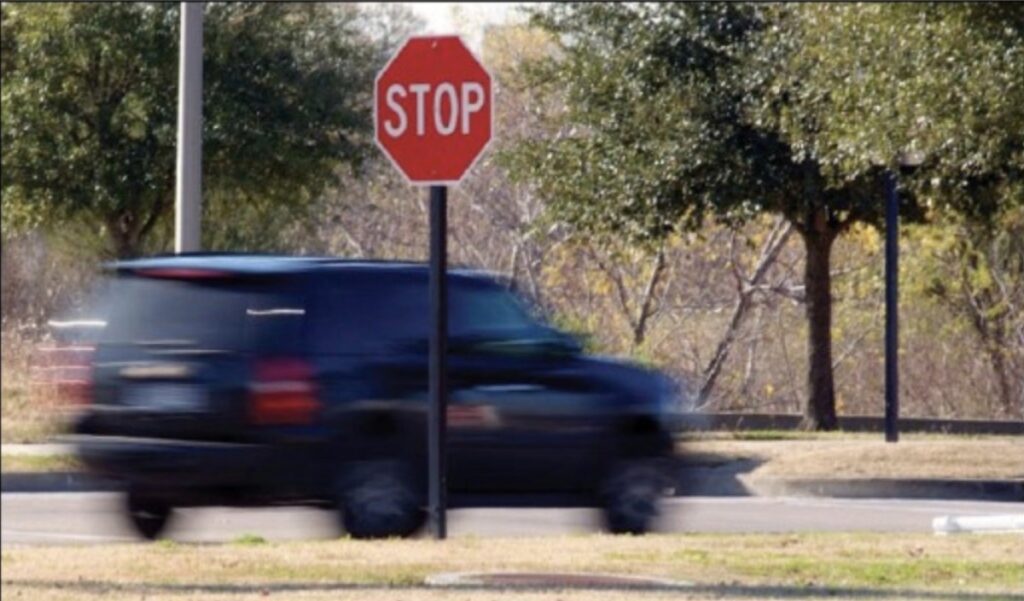

3. Pass a Stop as Yield Law

In 1982, Idaho passed a Stop as Yield law for cyclists—the first law of its kind in the nation. And for the next 35 years, Idaho remained the only state in the nation with a Stop as Yield law on the books.

Not for lack of trying.

Across the nation, numerous efforts were made to pass Stop as Yield legislation in other states. And every effort went down to defeat as bills were introduced, only to be rejected by the legislatures. For decades, it seemed as if Idaho would be the only state in the nation with a Stop as Yield law. In 2017, California looked like it might be the second state to pass a Stop as Yield law, but that effort too was defeated like all the other efforts in other states.

Maybe people just needed time to get used to the idea.

And maybe California just wasn’t ready to lead the way out of that legislative logjam, because the same year that California’s Stop as Yield effort went down in flames, Delaware passed a limited version of Stop as Yield. The logjam had finally been broken. Two years later, Arkansas and Oregon joined the ranks of states that had passed a Stop as Yield law.

The logjam had been broken. Will California be the next state to pass a Stop as Yield law?

Despite the lack of legislative will in 2017, I believe California could be the next state to pass a Stop as Yield law, and advocates should try again. Here’s why:

1. Stop as Yield Makes Sense.

Stop as Yield has some very powerful arguments in its favor. While opponents imagine a nightmare world of a lawless free-for-all on our roads, that imaginary world of chaos could not be further from the truth.

In reality, Stop as Yield actually keeps both cyclists and motorists within the framework of the law, while recognizing the inherent differences between bicycles and cars. This is a more rational approach to law and safety than our current approach, in which we insist upon a “Same road, same rules” logic, even though that isn’t actually logical because of fundamental differences between bicycles and cars. The more rational approach to the law would be “Same road, same rights, different rules.”

The reason this is the more rational approach is because bicycles inhabit a kind of middle-ground between a pedestrian and a motor vehicle. They’re not exactly like a pedestrian, and they’re not exactly like a motor vehicle either. They’re neither. They’re bicycles, with their own particular characteristics, and the laws should reflect that reality.

We understand this easily when we distinguish between pedestrians and drivers, so we don’t insist that pedestrians follow all of the rules for motorists. One particularly relevant example of this legal distinction between pedestrians and drivers is that pedestrians are not required to stop at stop signs. Likewise, we don’t make motorists follow all of the rules for pedestrians. So why do we insist on shoehorning cyclists into rules that aren’t a good fit? Why don’t we have rules for cyclists that recognize that we’re neither pedestrians nor motorists, while still respecting our rights to the road?

This is not even a radical idea. The law already states, for instance, that in California cyclists can take the lane when they are riding at the normal speed of traffic, but must ride to the right when they are riding at a speed that is less than the normal speed of traffic. This is a clear example in California law that we do in fact recognize that bicycles and cars are not exactly alike, and therefore, will sometimes have different rules. Because there are differences between our different modes of transportation, it’s more rational to conform the rules of the road to people, than it is to try to conform people to the rules of the road.

OK, but why do cyclists need a different law when it comes to stop signs? Why can’t they just stop like everyone else? Well, cyclists can stop, but that doesn’t mean that the law should require them to stop. Pedestrians can stop too, but the law doesn’t require them to stop. And in fact, it’s far easier for a pedestrian to stop than it is for a cyclist to stop.And it’s also far easier for a driver to stop than it is for a cyclist to stop.

That’s because of the inherent differences between a pedestrian, bicyclist, and a motorist. And some of the main differences involve the conservation of momentum and its effect on stability. When a pedestrian comes to a stop, the pedestrian momentarily loses momentum, but that has no effect on the pedestrian’s stability. The pedestrian can come to a complete stop, start walking again, and have exactly the same stability throughout the walk-stop-walk cycle.

Likewise, when a driver comes to a full stop, and then starts again from a full stop, he only has to press the gas pedal a bit, and off he goes. The driver has lost momentum, but has not lost stability, and is able to start moving forward again with virtually no physical effort and no loss of stability.

In other words, neither conservation of momentum nor stability are relevant concerns to either pedestrians or motorists.

But when cyclists start from a full stop, they have to call ontheir muscles to get them back up to speed and across the intersection. This means that they have the least amount of momentum and stability just as they’re entering and crossing the intersection.

It would be easier and safer if cyclists could just maintain momentum when there’s no cross-traffic. But because stop signs are often ubiquitous on the less-busy streets cyclists often favor, it’s often illegal for cyclists to maintain momentum. They’re required by law to come to a complete stop, even when there’s no cross-traffic. This is not only unnecessary for safety, it’s actually less safe, because cyclists are at their least stable when entering the intersection from a dead stop.

It would be far safer for a cyclist to slow to a reasonable speed when approaching the intersection, and stop if necessary for safety, yield the right-of-way when required, and roll through without stopping or yielding when the law allows. This is exactly how a yield sign works, so again, it’s not even a radical concept.

And there are 35 years of data to back this up. The Idaho Transportation Department has reported that there has been “no discernible increase in injuries or fatalities to bicyclists” as a result of its Stop as Yield law. In fact, in the first year after Idaho passed its Stop as Yield law, injuries to bicyclists actually decreased by 14.5%. Decades of real-world experience on Idaho’s roads have demonstratedconclusively that Stop as Yield is safe.

Finally, in an era of climate change, it’s more important than ever to encourage cycling as one of our means tocounter rising levels of atmospheric CO2. And that means we need bicycle-friendly policies, including safe infrastructure and common-sense laws that increase cyclist safety and encourage people to ride. There is nothing “bicycle-friendly” about infrastructure that decreases cyclist safety and penalizes people who are trying to ride by making bicycling as difficult and as possible. “Bicycle-friendly” must mean that cycling is encouraged by actions, not just words. It must mean that we encourage cycling by making it safer and easier and more attractive, rather than more dangerous and more difficult and less attractive because of counterproductive punitive measures.And one place to start is by making it safer and easier for cyclists to legally cross intersections.

2. The Arguments Against Stop as Yield Don’t Make Sense.

California’s Stop as Yield bill was opposed by powerful forces, including both the insurance industry and the Teamsters. But their arguments were nonsensical scaremongering. Consider:

AAA (the American AUTOMOBILE Association, in case you missed it) argued that Stop as Yield would be unsafe and “detrimental to all road users.”

This argument comes straight from an Alice-In-Wonderland up-is-down, water-is-dry alternate reality. There was a time when it was the automobile that was considered “unsafe and detrimental to all road users.” The automobile industry flipped that script with a relentless propaganda campaign that painted the pedestrians careless drivers were killing in droves as lawless “jaywalkers” and the crashes that careless drivers were causing as “accidents.”

Now, in that same vein, with a straight face and not a shred of evidence, the California branch of a national federation of motor clubs claims that it’s really cyclists yielding at intersections who pose a threat on our roads.

Well, can we get some data on that claim?

Nope. The opponents of the Stop as Yield legislation were as opposed to gathering data about Stop as Yield as they were to passing a Stop as Yield bill.

In opposing Stop as Yield, AAA was repeating a century of automotive propaganda that smeared the victims of careless and reckless drivers as “unsafe.” But the truth is that drivers not only break the law more often than cyclists, they are also by far the greatest danger on our roads.

The Teamsters had a different argument: Stop as Yield“would insert unpredictability into the traffic safety equation.”

This argument betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of what stop signs and yield signs are meant to do. When a driver arrives at a 4-way intersection controlled by stop signs, and someone in cross-traffic arrives at more or less the same time, they both have that moment of uncertainty when they’re trying to decide who has the right of way, and wondering whether they both agree on that point.

Well, what about when one of those drivers is facing a yield sign? There’s still that moment of uncertainty, when both drivers try to decide who has the right of way. And that’s the point of stop signs and yield signs—that uncertainty is not only completely normal, it creates the momentary pause that is necessary for people to safely get through the intersection. Replace some of the stop signs at that intersection with yield signs, and you still have the uncertainty necessary for people to safely enter and cross intersections.

Although the opponents of Stop as Yield are powerful interests in California, their arguments against Stop as Yield are weak, based on prejudice and resistance to change, rather than rational argument or sound judgment.

But times have changed. Even in 2017, opposition to the Stop as Yield bill wasn’t universal; the Editorial Board of the Los Angeles Times got the concept of Stop as Yield, coming out in favor of the legislation. There’s a sea change underway in how we think about Stop as Yield, in California and across the nation, and the logjam of opposition to Stop as Yield will break again. Will California be next?

3. There Will Never Be a Better Time Than Now.

After the 2017 legislative defeat, it might seem like we should wait for a more opportune time to re-introduce Stop as Yield legislation in the California legislature.

But there will never be a better time than now.

First, the 35-year legislative logjam has been broken. Stop as Yield is now the law in four states. Furthermore, one of those states has 35 years of data proving that Stop as Yield is safe. And the other 3 states? Chaos did not ensue, for two reasons: People already understand how to yield, and people are already treating stop signs as yield signs, and have been for years. In other words, on the day that Stop as Yield became legal in the other 3 states, things continued exactly as they had the day before, only now, cyclists were not risking a ticket when they yielded at stop signs.

Second, the politics have aligned for the better in California. Had Stop as Yield passed in 2017, it would have been sent to the Governor for his signature, and in 2017, the Governor was Jerry Brown, who proved himself to be something of a notorious anti-bicycle crank in his second incarnation as Governor.

But now, California has a new Governor, and his party holds a super-majority in the legislature. Governor Newsom flubbed it on the Complete Streets Act, but it’s still early in his first term and he still has time to get a bicycle-friendly California right. With Stop as Yield already the law in a handful of states, a super-majority in the California legislature, and a new Governor, we should give the Governor and the legislature the chance to get this right. There will never be a better time than now.

Third, climate change is upon us. Australia has been on fire for months. It’s estimated that a half billion animals have died in the fires. One of Australia’s iconic species, the Koala, has lost most of its habitat to fire and may be in danger of extinction. ACalifornia-based fire-fighting crew lost three of its team in the fight against Australia’s fires when their air tanker crashed while on the fire-fighting mission. This is the future we face if we don’t change course now. And a bicycle-friendly California is one of the easiest, least costly, and most healthy ways we can change course. There will never be a better time than now.

Copenhagen’s Climate-Friendly, Bike-Friendly Streets

***

For More Information:

Related Article: Origins of Idaho’s “Stop as Yield” Law

Related Article: It’s Time to Greenlight Stop as Yield

Related Article: Stop as Yield: Will California Be Next? Part 1

Related Article: Stop as Yield: Will California Be Next? Part 2